一篇发表在国际顶尖杂志 nature review上的文章,从 MDD 的流行病学、生物学和环境机制、管理和预防等方面进行了介绍,并概述了新兴研究以及 MDD 对日常功能和生活质量的影响。

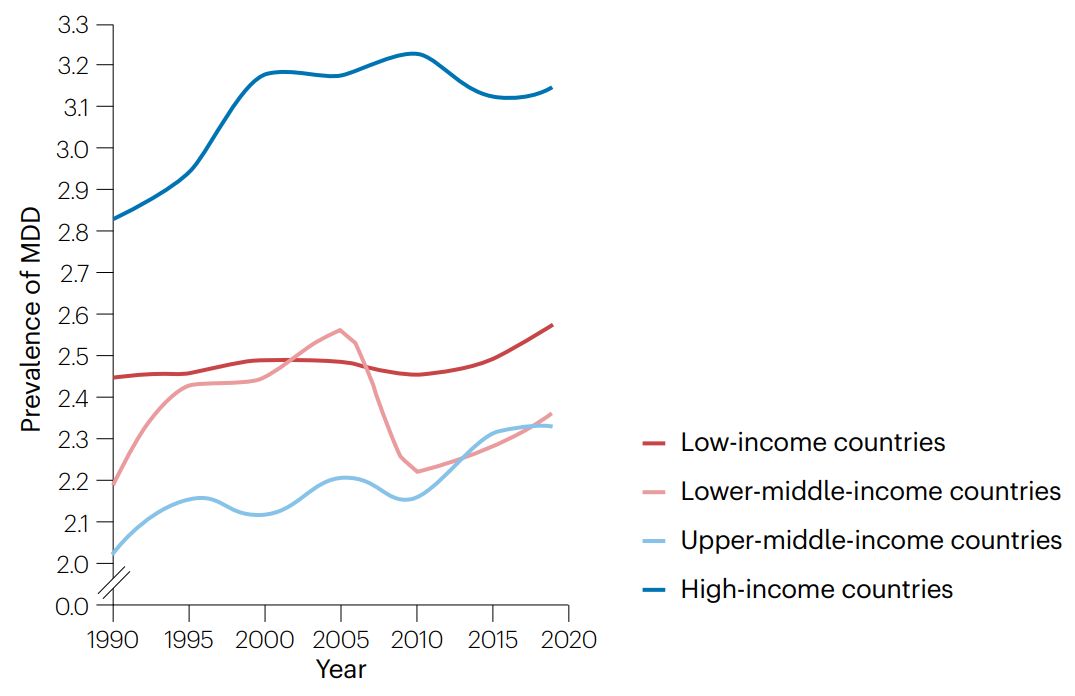

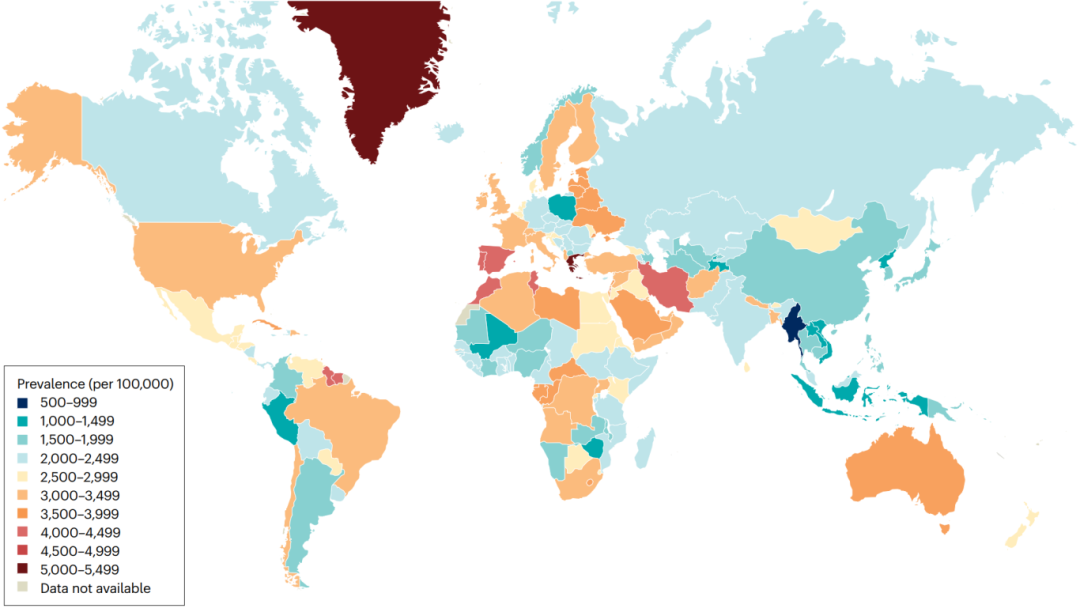

世界卫生组织调查显示全球抑郁症患病率约10%[2],但MDD患病率因研究设计和方法差异显著,可能低估真实值。前瞻研究揭示 MDD 终生患病率超 30% [3]。国家间 MDD 患病率各异,高收入与低收入国家略不同(图1),格陵兰岛和希腊最高,东南亚、大洋洲国家(如越南、所罗门群岛)较低(图2)。然而,受文化差异和方法学影响,这些差异是否“真实”尚待考究[1,4]。

图1 MDD全球不同地区患病率随时间变化

图2 MDD流行率的地区分布图

此外,MDD的患病率在全世界女性中几乎是男性的两倍,并且在整个成年期保持相对稳定[1,3]。患病率的性别差异可归因于生物心理社会因素的差异,包括生物和发育因素(如遗传和荷尔蒙差异)、心理因素(自我意识情绪的差异)和环境因素(如社会性别不平等)[5]。

MDD 通常出现在成年早期, MDD首次发病集中在 20-25 岁左右[5]。在社区调查中,抑郁发作的中位持续时间为 2-6 个月,超过70% 的抑郁发作在12个月内消退[6],但许多人仍处于缓解期。相比之下,在初级和二级精神卫生保健机构的研究中,大约 34-48% 的患者疾病持续时间超过 12 个月,且复发率非常高(在一些研究中高达 85%)[5]。抑郁严重程度越重、治疗前抑郁持续时间越长,可能导致抑郁发作持续时间也会更长。而抑郁发作前,身心功能较好的患者,可能持续时间更短[6]。

与一般人群相比,MDD 患者的并发症发生率更高[7]。自杀也是导致死亡率上升的一个关键因素。与无MDD患者相比,自杀死亡风险增加近20倍(95%CI 12.2–32.0)[8]。MDD 患者产生自杀意念、计划和企图的风险也更高[8]。

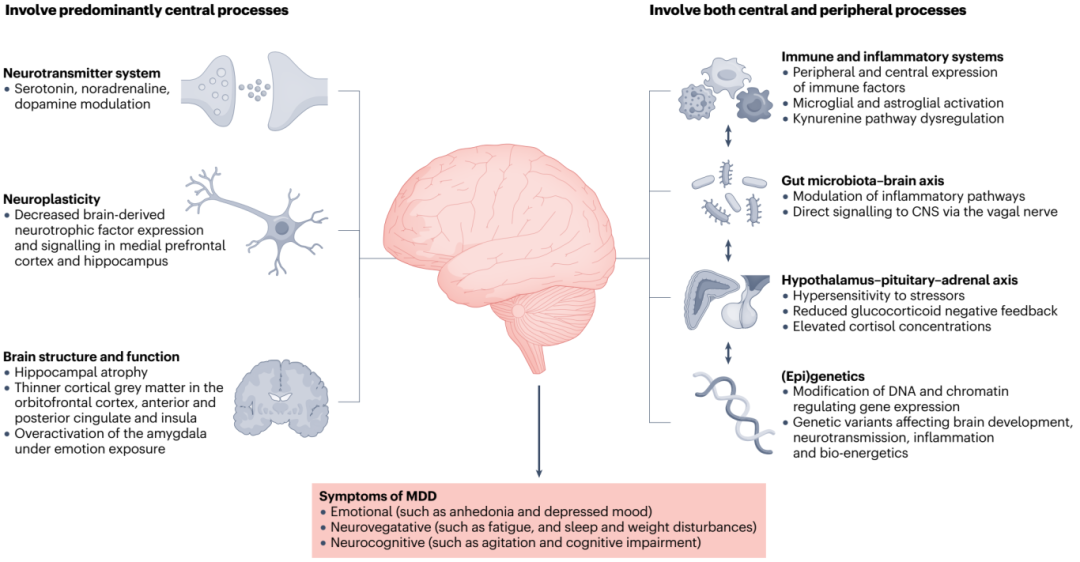

MDD是一种复杂的疾病;病因因素以及分子和细胞机制都与MDD的发生和持续有关。病因因素包括遗传和环境因素,发病机制包括大脑结构和功能、炎症、肠-脑轴和下丘脑-垂体-肾上腺(HPA)轴的改变。

MDD与自主神经系统(在应激条件下交感神经张力较高)、免疫系统和HPA轴的慢性过度活跃有关(图3).这些系统的失调是相互关联的,并且经常在MDD中同时发生[8,9]并可能导致 MDD 患者体细胞并发症的增加。

图3 MDD发病有关的生物学机制

HPA轴是一个主要的应激反应系统,能够适应生理和心理刺激,主要组成部分是下丘脑的室旁核,垂体的前叶和肾上腺皮质。HPA轴的异常活动是MDD研究和证实最多的生物学特征之一。

MDD 诊断的主要方法使用 DSM-5-TR 和 ICD-11中的操作诊断标准[18]。评估疑似 MDD 患者在过去 2 周内是否存在 MDD 症状。

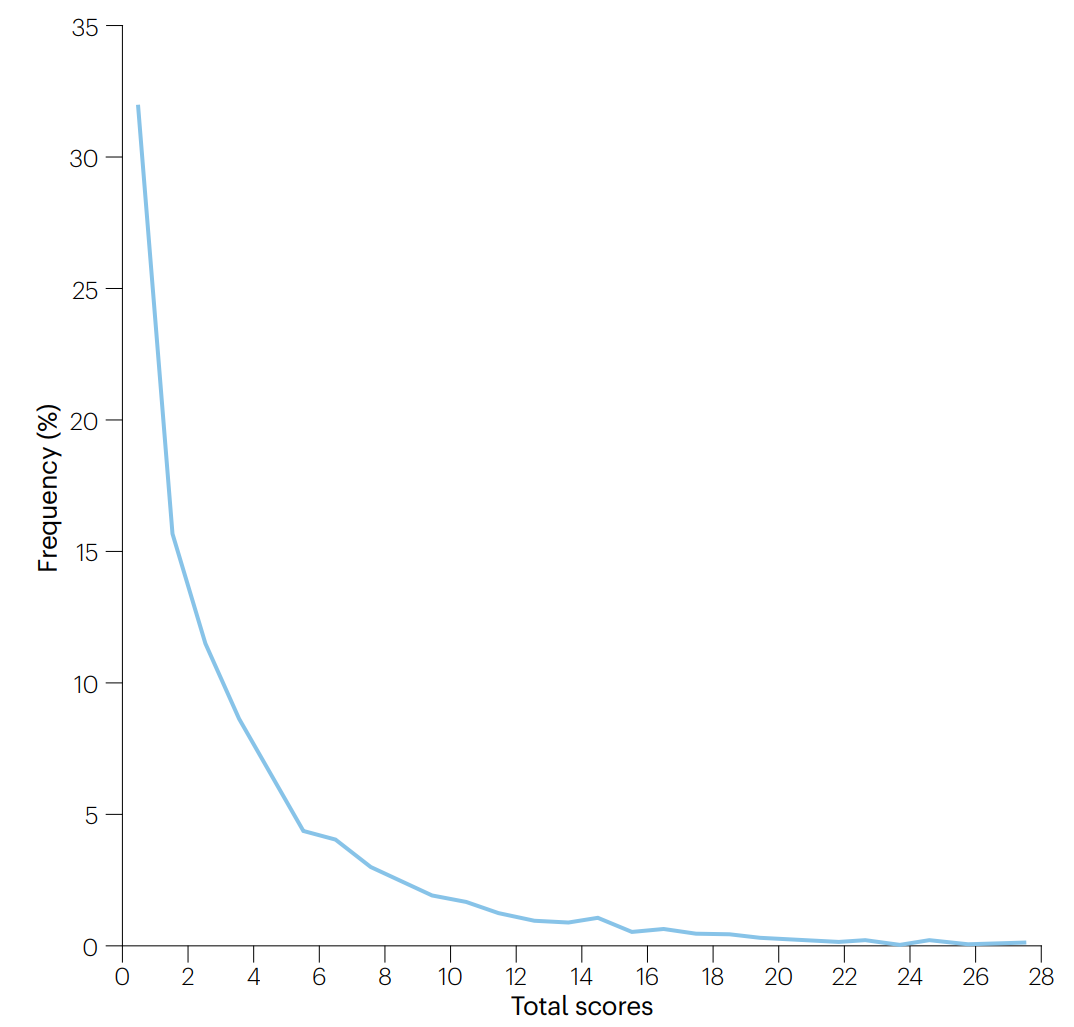

抑郁症状在一般人群中呈连续性(图4)。在将这些症状区分为有无临床表现会比较困难。明确的MDD诊断缺乏金标准,阈值以下的抑郁状态并不一定等同于完全的健康,并且这些抑郁状态可能与临床上重要的功能障碍有关。此外,这些症状是未来 MDD 诊断的危险因素,在一些研究中,估计有 3.8-18.9% 的阈值下个体在 1-3 年内发展为 MDD[19,20]。同样,对症状的治疗可以有效地改善抑郁症状和生活质量。

图4 PHQ-9总分在人群中的分布

MDD的预防主要分为三种:普遍预防、选择性预防(针对高危人群)和指示性预防(针对阈值下症状人群)。研究显示,对高危人群进行选择性预防,使一年内抑郁症发病率降低19%(95%CI 9-28%)[22]。学校预防计划中,针对高危人群的干预效果更佳。部分研究还证实,高风险抑郁症状青少年的初始发作率在有效心理干预后有所下降,并在葡萄牙一项为期24个月的青少年队列研究中得到重复验证[23]。

治疗差距(无法获得治疗的精神障碍患者的百分比)在高收入国家约为35-50%,而在低收入和中等收入国家高达85%。MDD患者的治疗机会和充分性也反映出这种差异[26]。原因之一是精神卫生工作者数量的悬殊:低收入国家每10万人不足1.4名,而高收入国家则超过62名[27]。在治疗供给上,71%的高收入国家超过75%的初级保健中心提供药物和社会心理干预,而中低收入国家这一比例仅为13%。政府财政对精神卫生保健的支持同样悬殊,中低收入国家人均仅0.37美元,而高收入国家则高达52.73美元[27]。

可用的心理治疗类型

多项研究证实,运动能显著改善抑郁症状[29]。每周2-3次、每次45-60分钟的中等强度有氧运动或阻力训练效果最佳[30]。在小组中监督运动,并依个人喜好调整,可提高运动依从性。

对于MDD,除了运动,其他生活方式干预也至关重要,如放松、工作调整、改善睡眠、正念训练等。同时,优化饮食、多接触绿色空间、戒烟和减少孤独感也有助减轻抑郁症状[30]。这些生活方式调整还有益于改善MDD患者的代谢和心肺健康,进而应对相关并发症[31]。

(正念训练和运动对抑郁症改善有效)

1. Global Burden of Disease Collaborative Network. Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Global Burden of Disease Collaborative Network

2. Scott, K. M., de Jonge, P., Stein, D. J. & Kessler, R. C. Mental Disorders Around the World: Facts and Figures from the WHO World Mental Health Surveys (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2018).

3. Moffitt, T. E. et al. How common are common mental disorders? Evidence that lifetime prevalence rates are doubled by prospective versus retrospective ascertainment. Psychol. Med. 40, 899–909 (2010)

4. World Health Organization. Depression and Other Common Mental Disorders: Global Health Estimates (WHO, 2017).

5. Kuehner, C. Why is depression more common among women than among men? Lancet Psychiatry 4, 146–158 (2017).

6. Ten Have, M. et al. Duration of major and minor depressive episodes and associated risk indicators in a psychiatric epidemiological cohort study of the general population. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 136, 300–312 (2017).

7. GBD Mental Disorders Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of 12 mental disorders in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Psychiatry 9, 137–150 (2022).

8. Cai, H. et al. Prevalence of suicidality in major depressive disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis of comparative studies. Front. Psychiatry 12, 190130 (2021).

9. Havinga, P. J. et al. Doomed for disorder? High incidence of mood and anxiety disorders in offspring of depressed and anxious patients: a prospective cohort study. J. Clin. Psychiatry 78, 13086 (2017)

10. Sullivan, P. F., Neale, M. C. & Kendler, K. S. Genetic epidemiology of major depression: review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Psychiatry 157, 1552–1562 (2000)

11. Osimo, E. F. et al. Inflammatory markers in depression: a meta-analysis of mean differences and variability in 5,166 patients and 5,083 controls. Brain Behav. Immun. 87, 901–909 (2020).

12. Mac Giollabhui, N., Ng, T. H., Ellman, L. M. & Alloy, L. B. The longitudinal associations of inflammatory biomarkers and depression revisited: systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. Mol. Psychiatry 26, 3302–3314 (2021).

13. Lee, C. H. & Giuliani, F. The role of inflammation in depression and fatigue. Front. Immunol. 10, 1696 (2019).

14. Patten, S. B., Marrie, R. A. & Carta, M. G. Depression in multiple sclerosis. Int.Rev. Psychiatry 29, 463–472 (2017)

15. Cryan, J. F. et al. The microbiota-gut-brain axis. Physiol. Rev. 99, 1877–2013 (2019). A seminal review of the mechanisms, preclinical evidence and clinical trial data that have investigated the role of the gut–brain axis in psychiatry.

16. Rutsch, A., Kantsjö, J. B. & Ronchi, F. The gut-brain axis: how microbiota and host inflammasome influence brain physiology and pathology.Front. Immunol. 11, 604179 (2020)

17. O’Riordan, K. J. et al. Short chain fatty acids: microbial metabolites for gut-brain axis signaling. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 546, 111572 (2022).

18. World Health Organization. International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems: Alphabetical Index Vol. 3 (WHO, 2004).

19. Green, J. E. et al. Feasibility, acceptability, and safety of faucal microbiota transplantation in the treatment of major depressive disorder: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Can. J. Psychiatry 68, 315–326 (2023).

20. Liu, R. T., Walsh, R. F. & Sheehan, A. E. Prebiotics and probiotics for depression and anxiety: a systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled clinical trials. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 102, 13–23 (2019)

21. El-Den, S., Chen, T. F., Gan, Y.-L., Wong, E. & O’Reilly, C. L. The psychometric properties of depression screening tools in primary healthcare settings: a systematic review. J. Affect. Disord. 225, 503–522 (2018).

22. UK National Screening Committee. Screening for Depression in Adults. UK National Screening Committee

23. Matos, A. P. et al. Prevention of initial depressive disorders among at-risk Portuguese adolescents. Behav. Ther. 50, 743–754 (2019).

24. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Depression in Adults: Treatment and Management (Update). National Institute for Health and Care Excellence

25. Kok, R. M. & Reynolds, C. F. Management of depression in older adults: a review. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 317, 2114–2122 (2017).

26. Thornicroft, G. et al. Undertreatment of people with major depressive disorder in 21 countries. Br. J. Psychiatry 210, 119–124 (2017).

27. World Health Organization. Mental Health Atlas 2020. WHO (2021)

28. Cuijpers, P. et al. Psychologic treatment of depression compared with pharmacotherapy and combined treatment in primary care: a network meta-analysis. Ann. Fam. Med. 19, 262 LP–262270 (2021).

29. Schuch, F. B. et al. Exercise for depression in older adults: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials adjusting for publication bias. Braz. J. Psychiatry 38, 247–254 (2016).

30. Marx, W. et al. Clinical guidelines for the use of lifestyle-based mental health care in major depressive disorder: World Federation of Societies for Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) and Australasian Society of Lifestyle Medicine (ASLM) taskforce. World J. Biol. Psychiatry 24, 333–386 (2022).

31. Firth, J. et al. The Lancet Psychiatry Commission: a blueprint for protecting physical health in people with mental illness. Lancet Psychiatry 6, 675–712 (2019).

32. World Health Organization. Comprehensive Mental Health Action Plan 2013–2030 (WHO, 2021)

33. Espie, C. A., Firth, J. & Torous, J. Evidence‐informed is not enough: digital therapeutics also need to be evidence‐based. World Psychiatry 21, 320 (2022).

34. Milaneschi, Y., Lamers, F., Berk, M. & Penninx, B. W. Depression heterogeneity and its biological underpinnings: toward immune metabolic depression. Biol. Psychiatry 88 369–380 (2020).

35. Lynch, C. J., Gunning, F. M. & Liston, C. Causes and consequences of diagnostic heterogeneity in depression: paths to discovering novel biological depression subtypes. Biol. Psychiatry 88, 83–94 (2020).

36. Glen, S., Simpson, A., Drinnan, D., McGuinness, D. & Sandberg, S. Testing the reliability of a new measure of life events and experiences in childhood: the psychosocial assessment of childhood experiences (PACE). Eur. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 2, 98–110 (1993).

37. McGorry, P. D. & Hickie, I. B. Clinical Staging in Psychiatry(Cambridge Univ. Press, 2019)

本图文源自网络,如有侵权,告之即删!